A More Inconvenient Life

If, like me, you’ve been getting up close and intimate with your household waste lately, one thing becomes clear almost immediately: we have an issue with convenience.

“Convenient travel-size”, “handy packs”, “quick and easy”, “single serve”. Convenience drives almost every purchasing decision we make, creating a habitual feedback loop: it’s easy to use, so we use it more often, creating a habit, making it easier to keep using it.[1]

At the Terracycle stall at the Woodend and Macedon Farmers’ Markets, consumption patterns are apparent in the popularity of items being recycled through the scheme. For one thing, either we’re all taking up free dental samples, or we’re travelling a LOT as mini-floss containers and tiny toothpaste tubes make up a significant portion of collected dental items.

And we have to have a serious talk about coffee pods.

Each and every market day, people tell me how relieved they are now they can recycle all those pods. “We fill up a bin-load of these things every week at work”, or “I do feel guilty using pods, but I’m a coffee snob” (Just quietly, you may want to ask some Italians or Ethiopians how they feel about coffee made with pods).

Such is the power of convenience that we’re otherwise content to dump a mountain of pods into landfill for the joy of a “café style” coffee at home. What happens if and when Terracycle decides not to offer this recycling stream any longer?

They don’t make ‘em like they used to

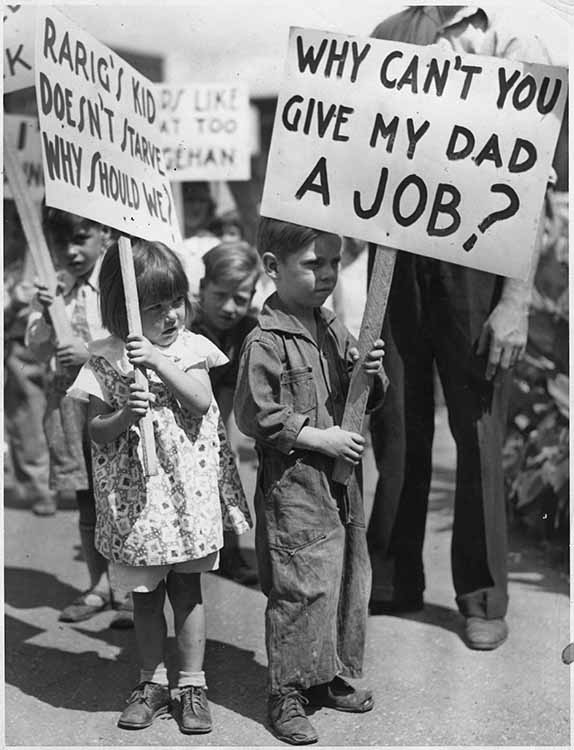

Modern convenience initially came in the form of time and energy-saving devices. Washing machines replaced mangles, vacuum cleaners replaced rug beaters, the fridge overtook the meat safe and cars zoomed past the horse and cart. These modernities promised a utopian vision where money would buy us time and freedom. Then came the Depression era, which gave rise to an economic model we are still struggling to break free of today. Needing to create jobs and kick-start economic growth, manufacturers deliberately started making cheaper products of less durable quality, made to be replaced. This successful model of consumption has been the driving force of the global economy for nearly 100 years.[2]

If the idea of planned obsolescence seems a bit like tinfoil hat, conspiracy-theorist territory, then it is worth considering that the electric lightbulb was one of the very first victims of this manufacturing sabotage. In 1925, electricity corporations in Europe and the USA met in Geneva to form a cartel that deliberately controlled the incandescent bulb market. They agreed to make the bulbs cheaper and with a shorter life expectancy, in order to force consumers to buy more bulbs, more often, thus driving the economy.[3]

Has convenience been all bad? So many time-saving products and devices have been marketed towards women over the years, all with the promise of making it easier to combine work and domestic life. But have cheaper vacuum cleaners, disposable wipes and TV dinners delivered gender equality? According to the Australian 2016 Census, women continue to do 5 – 14 hours more unpaid work per week than men. Perhaps there’s more money to be made by maintaining an unequal division of labour?

Modern addictions to sugar, plastics, fast food, fast fashion, smart phones, coffee pods, travel-sized, single-use products and packaging combine to illuminate our overarching addiction to convenience. But convenience is a myth that has led to the very real drudgery of managing mountains of waste produced by endless consumption. Not to mention the existential threat of climate change brought about by burning of fossil fuels.

Convenience vs Resilience

All this convenience is denying us an essential requirement of the human condition: to experience difficulty and challenges in order to adapt our behaviour and learn resilience.

Being surrounded by convenience doesn’t teach us how to cope in the face of adversity, no matter how mild. What would you do if you were thirsty and couldn’t immediately buy a bottle of water? Or if you had to navigate your way through an unfamiliar city without Google Maps? How did you manage before you could pop a pod in the machine whenever you wanted a coffee?

We have lost so much in this age of convenience. Baking your own bread is seen as a quirky, millennial hobby, rather than an essential life skill. It seems ludicrous now to painstakingly browse the stacks in a record store to discover new music when Spotify or Apple Music can immediately work out a playlist based on what you already like to listen to. What has happened to the atmospheric, ancient ritual of brewing coffee or the time taken to drink it? I remember when we would go and sit in an old style coffee shop if we wanted a hot drink while out and about. A quiet moment to pause and reflect. But now there’s an app for that, and who has time anyway?

Some climate scientists believe that we are passed the point of climate mitigation, and that only by adapting will we survive the climate-driven disasters to come.[4] But how adaptable are we after nearly a century of increasing and all-consuming convenience?

If modern consumption, driven by planned obsolescence and increasingly personalised buying habits, originated out of a desperate plan to escape a global crisis – the Depression – can we not come up with a plan now, in this moment of existential crisis, to change tack? This is our greatest challenge, and we need to be ready to adapt and develop resilience. Time to embrace a little inconvenience.

[1] The Tyranny of Convenience, Tim Wu, The New York Times Feb 16 2018.

[2] Planned Obsolescence: Engine of the Consumer Economy. Stuff You Should Know podcast, 25/6/2019.

[3] Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America, Giles Slade, Harvard University Press

[4] Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy, Professor Jem Bendell BA (Hons) PhD IFLAS Occasional Paper 2, July 27th 2018